January 1926

It is harder than ever for Helen and Doris to find time together. Helen understands: Doris’s affair with Milton consumes more and more of her life. But she misses the sleepovers in Doris’s apartment—the brave attempts at homemade Italian food and the red wine in gallon jugs and the man-sized breakfasts that always pose a challenge to her hangover the next morning.

And then yesterday, Friday, just before lunch, a uniformed messenger arrived on the set. Helen is finishing up a small comedy: a humdrum vehicle called Watch Your Wife. It will be one of her last film roles in New York before her move to California. She wishes the role could have been bigger, could have given her more momentum.

Maybe her career will take off out west. There certainly isn’t much about New York that she’ll miss. Except Doris. Nowadays when she has to emote for the camera, she only has to think about leaving her friend forever and the tears well up and spill over.

The messenger was in no hurry to leave the set. Eyes wide and mouth agape, he watched the shoot, waiting for the scene to end. Then, tentatively, maybe expecting to be scolded for intruding, he stepped forward and handed her an envelope with her name on it. Inside was a note in Doris’s handwriting: Milton’s going out of town this afternoon. Come over!

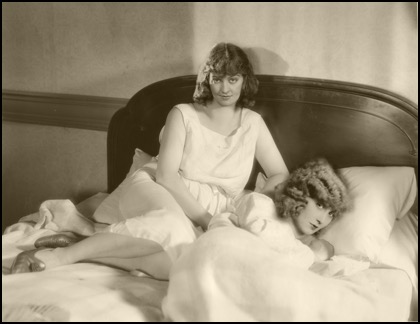

They are talking in bed this morning as they always do. Helen is lying on her left side, listening to the rain hit the skylight, watching rivulets snake down the frosted glass and distort the embedded mesh of wires they are passing over. She is listening to Doris talk behind her. Sometimes Helen makes small comments in response. Mostly she stays still and lets the musical voice wash over her much as the water glides by overhead.

This morning Doris is lost in reverie. She is talking about Dorothy Sills’s recent visit. She turns it over in her mind. She sometimes forgets that she is talking out loud. Helen listens.

“Milton said it was simply dreadful. He takes the ferry over to Hoboken to meet up with a little girl whom he hasn’t seen for a year and a half. She’s crying, aunt and uncle on his wife’s side are furious with him and refuse to leave him alone with her—as if he’s some sort of danger to his own daughter, for goodness sake!—and she’s begging him to come back to her and Gladys.”

This sounds like a pause. Helen waits an extra beat to be sure and then responds. “I still don’t get the idea of putting a ten-year-old girl on a train and sending her all the way across the country by herself. That’s the train I take to Hollywood. It’s not easy, for sure. You have to change halfway across, in Chicago or St. Louis, so even if the railroad people are looking out for you, which they don’t, really . . .”

“Exactly,” Doris interrupts, picking up her thought where she left off. “What was Gladys thinking? And she had already filed for divorce, so she wasn’t expecting to be reconciled. Probably her lawyer put her up to it. But what if something had happened to Dorothy on the way out here? And then of course she had to go all the way back by herself, too. Simply awful. Anyway, she got home safe and sound, so at least we don’t have that to worry about.”

“Thank goodness.”

“Which is not to say that Milton hasn’t been worried sick over it. He truly loves that little girl and would do anything to make her happy. Well, almost anything. I mean, he certainly wouldn’t go back to Gladys. Even before he met me, I mean.”

“And now even more so.”

“But he’s a brooder, Helen. He gets all bottled up with his frustrations and anger. I worry about his health. I honestly do. He’s worrying himself sick over this.”

This gets Doris talking about her own attack of appendicitis, seven months earlier. She nearly died. No one understood how serious her condition was until the poisoned thing actually burst inside her and she had to be rushed to the hospital. “That’s when I first realized that he truly loved me,” she says. She rests a hand on Helen’s right hip and pats it lightly. “He came to the hospital constantly around his shooting schedule. He paced up and down the halls, fretting about me, frantic to see me. And that was before anybody suspected that there was something going on between us. He was taking a big risk. For me. I’ll never forget that.”

“Because he loved you.”

“That’s when I knew we had something special, that we were more than just an item.”

“Because he loves you. You are so lucky.”

“I know, I know. First, I didn’t die! And he took such good care of me. And they even held up the filming of that movie, The Half-Way Girl, until I recovered. I was sure they’d just dump me and go with someone else, but they didn’t.”

Helen remembers the title but not much more. “The Half-Way Girl. That was the one where they blew up a ship at the end? A real ship? I read about that.”

Doris laughs. “Yes. Very dramatic. Very silly. There was a madman chasing me around the ship, and then someone let the leopard out of its cage—no one ever explained why there was a leopard on board or why someone let it out—and then the ship caught fire, and then after I was rescued by the hero and we were floating away to safety on a raft, the ship blew up, I assume along with the madman and the leopard. Very dumb. But I memorized a line from my favorite review. Do you want to hear it?”

“Of course.” Helen rolls over to face her friend.

“From the Los Angeles Express. The reviewer writes, ‘There is a spectacular touch to the fire at sea, although the fire burns a seemingly long time before the dynamite aboard hears of it and decides to demolish the vessel.’ Brilliant!”

They both clap, laughing. “O.K., now I have a serious confession to make,” Helen says solemnly. “I never saw that one.”

“Oh, dear,” Doris replies. “What are friends for, if not to see the terrible movies their friends are in?”

“I think I was driving a car onto a roof at the time. So explain it to me. What is a halfway girl?”

Doris sits up and crosses her legs Indian-style, shoving the folds of her nightgown down between them. “O.K.,” she says. “My character was named Poppy La Rue. Stupid name, right? She is an innocent chorus girl—“

“Uh huh. Right.” Helen snickers.

“—who finds herself stranded in darkest Shanghai and forced to work in a bar on infamous Malay Street. They call her a hostess, and you just know that if she stays there much longer things are going to turn out very badly for her. Anyway, at one point, Poppy explains what a ‘halfway girl’ is to the down-and-out hero. I remember that line.”

“Wait—how can you remember a line?” There wouldn’t have been much of a script, if any. “Did you actually have to memorize it?”

“No, no. It made it onto a title card. It just stuck in my brain.”

“Ah. Got it.”

Doris strikes a pose, both hands alongside her left ear. “’I’m not a bad girl,’ Poppy says, ‘not a good girl, just a halfway girl, half good impulses, half bad impulses.’ Actually, Poppy looked pretty much like a bad girl for the first part of the movie. Her dress kept falling off her left shoulder and she smoked and drank like a fish. Later on she looked more like a good girl. But then out on the high seas, she was generally soaking wet. Which as we know can make a good girl look like a bad girl.”

“Maybe,” Helen muses, “maybe she was unhappy because she wasn’t one thing or another. Because she was only a halfway girl. Maybe if she had been all bad or all good she would have been happier.”

Doris calls her in to breakfast. Today Helen is not hung over and she is looking forward to one of Doris’s big meals. Walking into the tiny kitchen, she puzzles over the heavy white bathrobes hanging off the backs of the kitchen chairs. They don’t usually wear robes around the apartment except when the heat is off and the wind is blowing in through the leaky windows, which it isn’t today thank goodness. She sits down and almost immediately a grand piled plate of food appears in front of her. Doris pours coffee and orange juice.

“Doris, what’s this?” She points at a small grey puddle off to one side of the plate. The puddle is half obscured by scrambled eggs and overlying strips of bacon.

“Those are grits, of course. I made them especially for you, for your birthday, which I happened to remember is tomorrow. All southern girls like grits, right? Although I admit those grits don’t look very appetizing.”

“Well, they don’t look like any grits I’ve ever seen. And you didn’t have to get me a birthday present. But I love you for making that effort, and I’m going to eat them up right now.” She picks up her fork.

“No, no, no, wait,” Doris exclaims, putting a hand on Helen’s forearm. “First I want to propose a toast.” She goes the refrigerator, pulls out a small bottle of champagne, and puts it on the table next to the orange juice. Then she takes two champagne flutes out of the china cabinet. “Yuk,” she says, inspecting them. “Hold on. Sorry. Your breakfast is getting cold.” She washes and dries them quickly, puts them on the table, and sets to work on the champagne cork.

“Isn’t it a little early, Doris?” For you, Helen thinks. Not for me.

“No, no,” Doris replies. “It’s never too early for a Saturday morning mimosa.” She takes the basket off the bottle carefully, and then puts her napkin over the cork and begins twisting it slowly. Out from beneath the napkin comes a crisp pop. She holds up the bottle and a tiny vapor cloud emerges from its neck. “Which do you put in the glass first—the juice or the champagne? I don’t remember.”

“I bet it doesn’t matter.”

“O.K., then. Champagne first, then juice.” The bubbles rush to the very tops of the flutes and then spill over. She adds the juice. “Oooh. Nice color, don’t you think?”

“Yes. Nice. So what are we toasting?”

“A toast,” Doris says, raising her glass, “to girls who commit themselves to something with all their hearts and ignore all the obstacles that the world throws up in front of them—things like leopards and fires and exploding ships and guys on rafts who are handsome but extremely dumb. To girls who happen upon other girls just like themselves and help them, just like we help each other. To girls who eat bad grits without complaining. To girls who aren’t halfway girls.”

Helen raises her glass. “Yes. Let’s drink to that, especially the last part. To girls who aren’t halfway girls.”

They drink the fizzy concoction in a few quick gulps and Doris refills their glasses.

They have finished their breakfasts. The champagne has gone directly to Helen’s head.

There’s a knock on the door. “Ah—the second half of your birthday present,” Doris says, smiling. She gets to her feet a little unsteadily and pulls on her robe. “Here, put yours on and come with me.”

Doris goes to the door, opens it enough to see who is there, and then lets it swing open. “Hi, Ed. Good to see you! And you must be Ed’s assistant. Do come in.”

Two men start making their way into the small vestibule, dripping wet and staggering under heavy burdens of cases and bags. The first one, Ed, looks familiar.

“Helen, I think you know Mr. Hesser. He’s taken your picture a couple of times in the past few years. He’s in from the Coast for a few days. Ed, you remember my friend, Helen Worthing.”

“Of course. Good to see you again, Miss Worthing.” He flashes an engaging smile at her as he slid his raincoat off. Looking left and right and not seeing an obvious place for the dripping coat, he sets it down on the floor. Then he looks back at Helen. “My goodness! Look at you. Still too beautiful for your own good. And this is Charlie, who’s going to help me set up.”

Charlie shuffles the rest of the way into the hallway like a large bear cub, nodding and grunting. He also drops his raincoat on the floor.

“Doris,” Helen says, “I’m confused. Set up what?”

“Ed is going to take a picture of the two of us. Before you go away. So we can always remember our good times together.”

“And unfortunately, Miss Kenyon,” Hesser says, “it’s going to be an indoor shot. It’s raining cats and dogs outdoors.”

“We’re fine with that. Helen, how should we pose? Do you have a preference?”

She hesitates. “Yes. But . . . I don’t want to embarrass you.”

“You won’t.”

“Well then, I would like to have our picture taken in bed, just like we were, with you talking and me just listening.”

Doris laughs. “Perfect! Especially because in this dinky apartment, there aren’t a lot of other choices. Gentlemen, this way, and Helen, you should probably wait here while I get them started. Not enough room for everybody all at once.” The two men follow her down the hall, clanking and bumping.

Helen walks over to the small mirror on the wall near the door. Oh god. She tries primping to no avail.

“Oh, Helen, relax. You look fine.” Doris has come up behind her and circled Helen’s waist with her arms.

“Ugh. I do not. I have to fix my hair and my eyes and my lipstick. Everything that’s going to show above the sheets. For this picture, I sure don’t want to be the halfway beautiful girl. I want to be the all-the-way beautiful girl. So you’ll always remember me that way.”

“The bathroom’s all yours. They’ll be a while setting up the lights.”

“What about you? Aren’t you going to get fancy?”

“I don’t think so,” Doris replies, squeezing Helen’s waist a little tighter and then sliding up just a little higher. “I’m going the other way. I’m going to be the all-the-way plain girl.” They both look at her reflection in the mirror. “The girl who snores and drools and looks just like this when you wake up next to her. Frumpy and unkempt. That way, you’ll never forget who that other girl in the picture is. You’ll say to yourself, Oh, I remember her—that’s Frumpy Kenyon.”

“Frumpy Kenyon,” Helen laughs. “Ha. That’ll be the day. Here—let go of me so I can stop looking at myself in the mirror and hug you back.”

She turns. They hug long and hard.

“So no halfway girls here,” Helen says.